The Neuroscience Supporting ICF Core Competency #2, “Embodies a Coaching Mindset”

Susan Britton, MCC

Embodying a Coaching Mindset

Every profession has tools of the trade: programmers have code, accountants have spreadsheets, project managers have flow charts, and,

Coaches have the ICF core competencies.

One could make the case that, among all of the eight competencies, ICF #2, Embodies a Coaching Mindset, is the bedrock of these tools. Why? In essence, as a coach…

You are the the most valuable tool!

Your SELF is the primary instrument being used in coaching. And the condition of you, as an instrument, affects how well you can employ all of the other competencies. Jessica Burdett, PCC, offers further insight on “Self as instrument”:

”Our ability to use the instrument is largely limited by

our ability to understand the capacity of the instrument,

and then by the level of skill we have developed in utilizing the instrument’s capacity.”

Without a well-tuned Self, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to demonstrate other “downstream” competencies. For example, during coaching performance evaluations, assessors evaluate ICF #2, Embodies a Coaching Mindset, via behaviors within other competencies: ICF #4, Cultivates Trust and Safety; ICF #5, Maintains Presence; ICF #6, Listens Actively; and ICF #7, Evokes Awareness.

Developing an underlying coaching mindset requires continual learning, and helps bring to life all of the other competencies. By exploring the neuroscience concepts of Blue Zone biology, neuroplasticity, and metacognition, we can better understand how we learn and recognize how mindsets develop.

Coaching Mindset: Definition and Development

ICF Core Competency #2, Embodies a Coaching Mindset, is defined as:

Develops and maintains a mindset that is open, curious, flexible and client-centered.

How do we fine-tune this type of mindset? ICF makes clear that embodying a coaching mindset is a process that doesn’t happen overnight! It involves “ongoing learning and development” (subcompetency 2.2) and takes place throughout the trajectory of one’s professional journey.

Core to embodying a

coaching mindset is a

LEARNING ORIENTATION

To successfully tune Self as an instrument, we can consider the lifelong learning that has shaped our current mindset.

-

- As babies, we naturally displayed the mindset of open and curious. There is an innate inclination to explore the world—to touch, explore, and examine, especially when there is a secure attachment with caregivers in a nurturing environment.

- As toddlers, we learned that not all of the world is safe: stoves are hot, cats can scratch, and heights can lead to falls. With a growing awareness that there are threats in the world, cautiousness tempers openness and curiosity. And if children grow up in environments that don’t foster safety and threats are manifold, curiosity can be replaced with disassociation or defensiveness in order to survive. Throughout these experiences, the brain strengthens its wiring, reinforcing our perceptions of safety and threat.

- As adults, our mindset is the product of a multitude of environmental influences and relational experiences. At some point in your coaching journey (or perhaps before), you learned that you have the power to choose and shape your mindset.

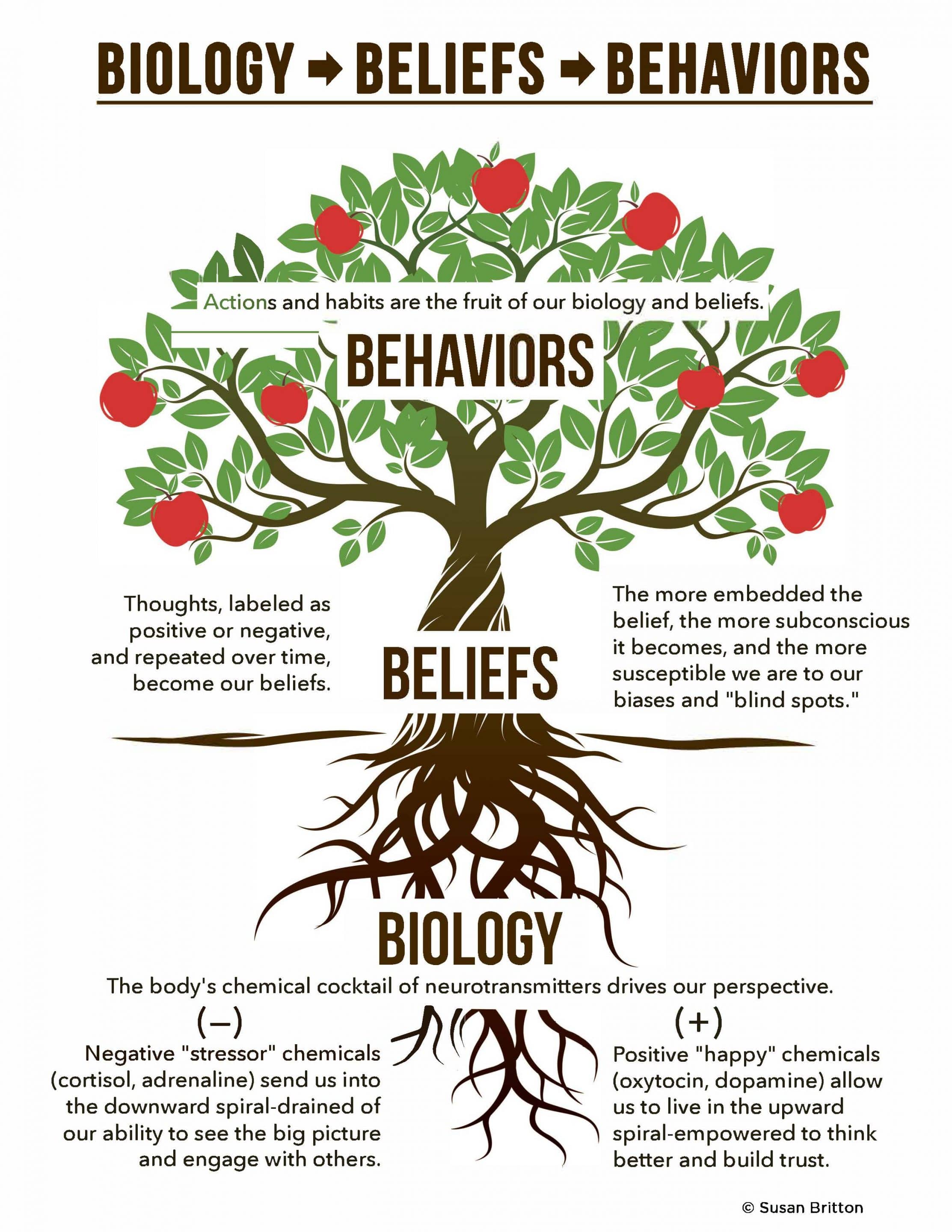

The central role of our mindset is outlined in the image below. When our biology is in a calm-connect state, it impacts our beliefs, or mindset. We are able to think better. And with better decision-making and cognitive organization, we can intentionally choose and habitualize behaviors that reflect a coaching mindset, such as openness, curiosity, flexibility, and client-centeredness. Over the long range, our mindset in turn also impacts our biology, influencing how our body is regulated, and inversely, how easy it is to maintain an open, curious, flexible, and client-centered mindset.

With this image in mind, we will look at three neuroscience concepts that relate to the learning orientation that supports a coaching mindset:

-

- “Blue Zone” Biology—the brain-body chemistry that enhances coaching mindset: A coaching mindset is influenced by our brain-body biochemistry. When heart rate, blood pressure, cortisol levels, and more are in a calm range, the parasympathetic nervous system is in charge. This system produces a relaxed feeling, which is conducive to an open and curious mindset.

- Neuroplasticity—strengthening and pruning of neural connections: Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and change, is essential for learning and memorizing new patterns of thinking, emotions, and behaviors. We can learn to strengthen and prune connections that reinforce a coaching mindset.

- Metacognition—awareness of and reflection on thinking and emotions: Metacognition is often described as thinking about your thinking and emotions. It requires an awareness and reflection on our cognitive and emotional processes, which in turn supports the flexible thinking required of a coaching mindset.

“Blue Zone Biology” Helps Embody a Coaching Mindset

Change can be hard work. It takes physical energy to strengthen synaptic connections and emotional energy to navigate the unfamiliarity and uncertainty of change. The body’s biological state can boost the energy levels required for change.

We refer to the Red Zone | Blue Zone model to contrast the differences in our cognitive and relational capacities when in these states. Red Zone is the threat state—energy is deployed to prioritize protecting and defending. Blue Zone is the connect-create state—energy can be channeled toward creative thinking and deepened relationships.

Two key aspects of our biology that can provide biological support for coaching mindset are the parasympathetic nervous system and the neurotransmitters involved in synaptic plasticity. These components lend support towards being in a coaching mindset, a Blue Zone space of openness, curiosity, flexibility, and client-centeredness. Briefly:

- Parasympathetic Nervous System: When the parasympathetic nervous system is predominant, cardiovascular activation is reduced. This is the rest-digest/calm-connect state that supports open and curious thinking. Conversely, if the sympathetic nervous system is in action, heart rate and respiration increases and adrenaline and cortisol are released. This is the fight-flight-freeze state, which can prevent us from thinking in an open, curious, and collaborative way.

To be clear, the sympathetic nervous system is not a ‘bad guy’—it can help us rise to the occasion. But our appraisal of situations is key. If we perceive we can handle a situation, we see it as a challenge, which helps us become more curious and open in our thinking about how to navigate the challenge. If we perceive we cannot handle it, we see the situation as a threat, triggering our biology to respond with fight-flight-freeze reactions. The proportion of appraisals matters. If our mindset is primarily appraising situations as threats, the sympathetic nervous system is continually triggered, which makes it difficult to regulate emotions (subcompetency 2.6, developing and maintaining the ability to regulate one’s emotions).

Another benefit of the parasympathetic nervous system is that it gives us access to top-down thinking. Dr. Bruce Perry, coauthor with Oprah Winfrey of What Happened to You?, describes that top-down thinking engages the brain’s neocortex—this area of the brain involves higher-order cognitive skills, such as strategic thinking, abstract thinking, and complexity thinking. He goes on to explain that the parasympathetic nervous system supports this type of thinking. Conversely, when the sympathetic nervous system is predominant, different parts of the brain take the lead in cognition, such as the limbic, midbrain, and brainstem areas of the brain. The mental processes associated with these areas lead to more emotional or reactive thinking. It would be difficult to have a client-centered coaching mindset when the sympathetic nervous system is in overdrive.

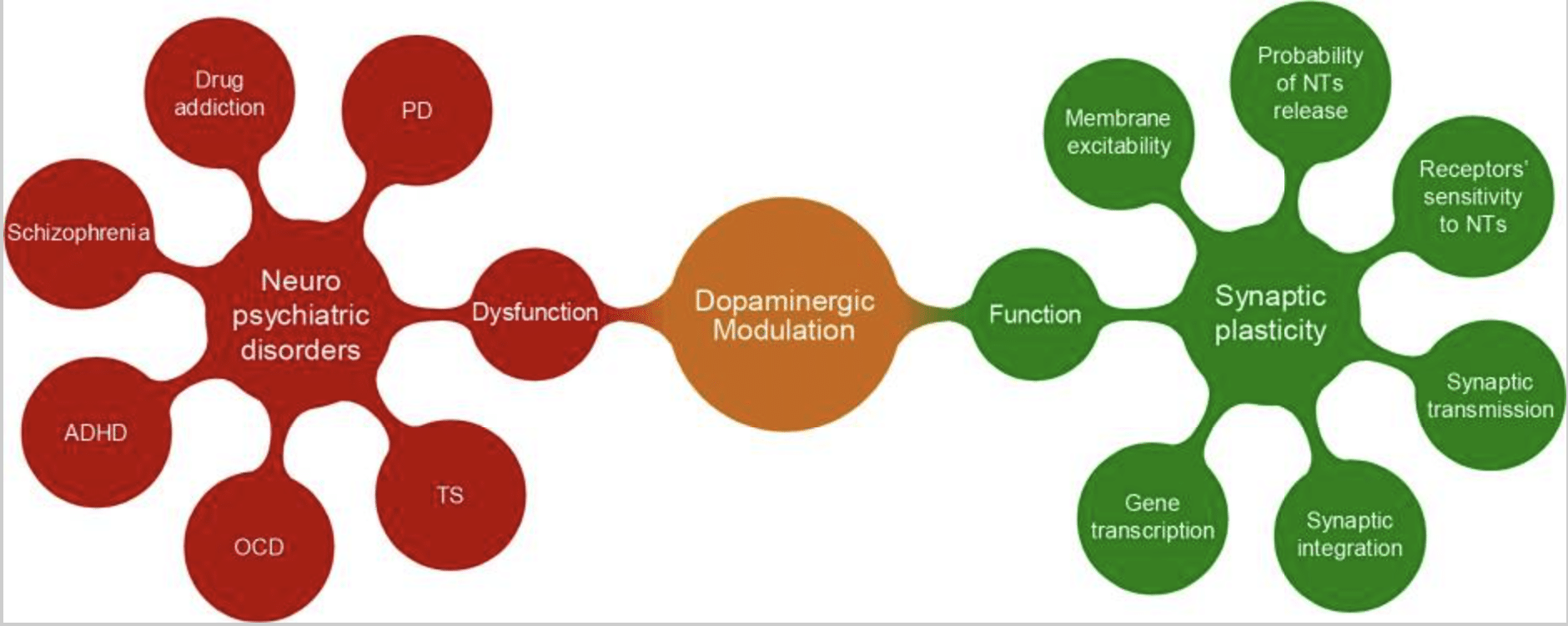

Neurotransmitters: Dopamine, the neurotransmitter involved in motivation and seeking rewards, also plays a key part in the brain’s ability to rewire itself. In recent research on dopamine’s involvement in strengthening neural connection, its presence was found to be one of the most important factors for enabling synaptic plasticity; conversely, impaired dopamine signaling is thought to be involved in several neuropsychiatric disorders, as the image below shows.

Moreover, positive emotion research by Barbara Fredrickson and Alice Isen points to improvements in mood, cooperation, and strategic thinking when “happy” neurotransmitters (e.g., oxytocin, dopamine, serotonin) are balanced and predominant. This is the parasympathetic nervous system at work. And conversely, when “crappy” neurotransmitters run the show (e.g., a prolonged and unnecessary spike in cortisol and adrenaline associated with the sympathetic nervous system) it is difficult, if not impossible, to be open, curious, and flexible!

With the foundation of Blue Zone Biology in mind, we can explore how neuroplasticity plays a role in strengthening a coaching mindset.

Neuroplasticity

“Everything having to do with human training and education

has to be re-examined in light of neuroplasticity.”

~Norman Doidge, M.D.

The Brain that Changes Itself

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to adapt and change. Some of the most marked descriptions of this changeability fall under the miraculous work of Dr. Paul Bach-y-rita, one of the physician-scientists described in The Brain That Changes Itself. In the book, Dr. Doidge describes some of the feats Bach-y-rita has accomplished:

-

- A 65-year-old victim of a severe stroke returns to college professorship. After the destruction of 97% of nerves running from the cerebral cortex to the spine, this individual (Bach-y-rita’s father) was taught by his son to first crawl, then stand, then walk, as well as talk, and eventually return to teaching college at City College in New York.

- Congenitally blind individuals see. Using a sensory-substitution device that fits inside the mouth, the device transfers the sensations to the brain but virtually creates new retina-like wiring to decode them into pictures . . . to the point that the blind individuals could make out the shape of a telephone hidden behind a glass vase, or determine whether someone’s mouth was open or closed.

- The woman who continually fell. With 95-100% of her vestibular function erased by an antibiotic administered for a postoperative infection, this 39-year-old could no longer stand or walk without falling. Often, even when crumpled on the floor, she could not find balance. After losing her international sales job, she was subsiding on a $1,000 monthly disability check and experiencing deep depression. Bach-y-rita developed a headgear system that retrained her brain to find its balance, and she was eventually able to wean herself from the device, while maintaining the balance the device retrained in her brain.

If the brain can rewire itself to accomplish such fantastic feats, can it not also rewire the mindset of thoughts, feelings, and actions that cause us to stumble and fall, figuratively speaking?

The answer is a definitive yes.

Neuroplasticity is essential to a coaching mindset because it is fundamental to learning. At the cellular level, neurons communicate with each other through specialized structures called synapses. A key aspect of learning and memory is synaptic plasticity—the ability of synapses to change in strength. This plasticity occurs through strengthening or weakening (and eventually pruning) of synapses.

-

- Strengthened Synapses—”Practice Makes Perfect”:

When two neurons are repeatedly activated together, the synapse between them is strengthened. Stronger synapses are the result of repetition, similar to the concept of creating muscle memory. After you practice something repeatedly, you have muscle memory and can repeat the task without much effort. Your brain can also operate without much effort, once the connections are strengthened. In fact, an international team of neurologists confirmed that people with high IQs have brains that work smarter, not harder. This is done through the efficiency, or strength, of their neural connections.

The technical term for this strengthening of synapses is long-term potentiation, or LTP. LTP is considered a cellular basis for learning and memory formation. The synapse grows stronger because there are increases in the neurotransmitters such as dopamine being released into the system.

- Strengthened Synapses—”Practice Makes Perfect”:

-

- Weakened or Pruned Synapses—”Use it or Lose it”:

When neurons are not used frequently, they become less efficient, and are eventually pruned.

The technical term for the weakening of synapses is long-term depression, or LTD. When synaptic connections get used less and less, they get marked by a particular protein. The brain has a sort of janitorial system that goes about cleaning up synapses when we sleep. Specifically, there are glial cells which detect the mark and bond to the protein to prune or destroy the synapse. Bottom line, if it hasn’t been used, it will be lost.

In coaching, we can think of these weakening connections as letting go of familiar, but unhelpful, thinking or emotions that do not support a coaching mindset.

- Weakened or Pruned Synapses—”Use it or Lose it”:

Note that there is a similar term to neuroplasticity, which is neurogenesis. Neurogenesis involves the birth of new neurons in the brain, which can occur through aerobic exercise, challenging mental activity, sleep hygiene, meditation, supplements, and more. Although neurogenesis is important for brain health, we are focusing this ICF #2 discussion on neuroplasticity, given its relevance for strengthening thinking patterns and emotional states.

With the reality of neuroplasticity, we have the physical ability to rewire our brain to continually deepen our capacity to embody a coaching mindset. We can also deepen this capacity via metacognition.

Metacognition

It’s been said that the brain is a ‘meaning-making machine.’ We take in information, interpret it, mix in emotion, and create narratives that help us make sense of what we see, hear, feel, and experience. These narratives make up our mindset!

As part of our learning orientation, it is incumbent on us to examine these narratives open-mindedly and curiously (subcompetencies 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, developing a reflective practice, remaining aware of contextual/cultural influences, using awareness of intuition to benefit clients). Metacognition can support these processes.

The common description for metacognition is “thinking about our thinking.” In more formal terms, metacognition comprises both the ability to be aware of one’s cognitive processes (metacognitive knowledge) and to regulate them (metacognitive control).

We rightly add thinking about our emotions to this discussion, since there is a major interplay between thinking and emotions. Vanderbilt University pathology professor Quentin Eichbaum, M.D., in his journal article “Thinking About Thinking and Emotions” explains that “Cognition affects emotion, and emotions in turn shape cognitive processes such as perception, memory, learning, and decision making.”

Thinking about our thinking and emotions is easier said than done because there is much below the surface that is not readily apparent: the unconscious elements of priming, automatic behavior, habitualized behavior, actions based on unconscious deliberations and more come into play.

Harvard Business School professor emeritus and former member of Harvard’s Mind, Brain, and Behavior Interfaculty Initiative, Gerald Zaltman proposes that “most of what we know, we don’t know we know.” He goes on to say that “Probably 95% of all cognition, all the thinking that drives our decisions and behaviors, occurs unconsciously.”

If just 5% of brain activity is conscious, how proficient can we be at thinking about things of which we are not consciously aware? The unconscious is elusive. Yale social psychologist John Bargh and San Francisco State neuroscience theorist Ezequiel Morsella describe this part of the mind as “a pervasive, powerful influence over such higher mental processes.”

When we are open and curious about our thinking, it can support deeper complexity of thinking. Psychologist Peter Suedfeld of University of British Columbia describes complexity of thinking as a cognitive style associated with “flexibility, high levels of information search, and tolerance of ambiguity, uncertainty, and lack of closure.” This flexibility in our thinking reflects a coaching mindset, equipping us to support clients in navigating the uncertainties of change.

Deepening Mindset Through Metacognition

Our behavior and reactions can clue us in that there are things happening under the surface that are not aligned with the coaching mindset we want to have. Metacognition first requires awareness of what is going on inside. For example:

-

- WHAT we think—the inner voice: What we think can include awareness of thoughts, emotions, desires, preferences, predictions, memories, hopes, dreams, goals, tasks, fears, frustrations, gratitudes, and more. It can be crowded and quite noisy inside our brain!

Using a scenario of a coaching call that didn’t go as well as you would have liked, there might be an inner narrative about whether you correctly implemented specific coaching techniques or maybe the narrative yields concerns about whether the client liked a challenging question you posed. Maybe you noticed an uneasiness rising about the session possibly going too long and the debate in your head about whether to interrupt and if so, how. You might worry whether the client is happy with their progress, whether they’d give you a good net promoter score, or maybe whether they’ll be successful experimenting with the new learning that was uncovered.

If we were to have a transcript of a coaching call that included our inner voice, it would be interesting to see what percentage of the conversation this voice takes up! - HOW we think—the patterns of the inner voice: At this level, we consider if there are prompts, predictions, and patterns that underlie the content of the narrative. What environmental or situational circumstances or people may have prompted this thinking? What perceptions or expectations may have been at play? What patterns do you notice in the thoughts?

Looking at another example, let’s say a coach is noticing that he’s thinking a lot about a couple of coaching clients who continue to ask for his opinion about the motivations of difficult team members, despite setting agreements about him being a coach and not a consultant. His expectation is that the clients will abide by this agreement, and when they don’t, he notices his own pattern of frustration at their “asks.” He also notices a pattern of rising uneasiness that they won’t find value in his work if he doesn’t also put on his consultant hat. Also part of the pattern, he notices that, against his better judgment, he tosses them a ‘bone’ of advice now and then, only to have it ignored. - WHY we think as we do—where the patterns stem from and whether they still serve us well: To be an archeologist of your unconscious, compassionately ask yourself, “What does this remind me of?” and see what associations arise.

Continuing with the above example, exploring patterns might reveal that the coach feels scared because he was raised in a family-of-origin that emphasized people-pleasing. The unconscious mindset emerges as, “I must provide a fix to be of value; I must make sure people are happy with me.” And to not people-please brings up a curiosity about the tension between abandoning his early family values yet wanting to honor the power of core coaching competencies and the tenet that the client is creative and resourceful.

- WHAT we think—the inner voice: What we think can include awareness of thoughts, emotions, desires, preferences, predictions, memories, hopes, dreams, goals, tasks, fears, frustrations, gratitudes, and more. It can be crowded and quite noisy inside our brain!

From a place of awareness, the next step is regulation. We can explore ways to actively practice expanding our coaching mindset. Through thinking about our thinking and emotions, we can be curious about perceptions and patterns, as well as be intentional about the new mindset muscles we want to develop moving forward.

With so much below the surface, it takes intentionality and perseverance to bring awareness to our thinking and emotions that have previously been unconscious. Coaches benefit from self-development work as part of their learning orientation—consider working with a coach to support you in bringing intentionality to your mindset and behaviors. Many coaches also advocate engaging a therapist to better examine beliefs and behavioral patterns born in youth that no longer serve in adulthood (this may be one example of subcompetency 2.8, seeking help from outside sources when necessary).

Coaching Mindset: Learning Orientation

Embodying a coaching mindset is found in a learning orientation. As we deepen our learning about Self as an instrument, we deepen our capacity to support clients. Incorporating basic tenets of Blue Zone biology, neuroplasticity, and metacognition will augment our capacity to embody an open, curious, flexible, and client-centered mindset. How will you tune your instrument today?

Susan Britton, PCC, is founder and president of The Academies for Coaching Inc., providing coaching education globally since 2001. For nearly 10 years, The Academies has been a leader at the intersection of coaching and neuroscience, with a commitment to curate and synthesize neuroscience findings into accessible, memorable, and effective coaching tools. Learn more about The Academies passion for “Changing Minds, for Good” at www.TheAcademies.com, where you can receive short, bi-weekly installments of “Encourage Your Brain”!

Our Courses

We offer all neuroscience-based programming; courses in career, leadership and strengths.

Encourage Your Brain!

Sign up for a free, short, brain-friendly newsletter that is guaranteed to make you feel better every Friday!