The Neuroscience Supporting ICF Core Competency #3, “Establishes & Maintains Agreements”

Susan Britton, MCC

Coaching Means Change

People come to coaching for change—they want something different, with the hope for a better future. Although change is a constant in life, the brain doesn’t easily embrace change. Our natural propensity to seek safety and predictability often causes stress as we navigate the unknown. And succumbing to stress can hinder our capacity to adapt and grow.

This article in our series on the neuroscience behind the ICF core competencies focuses on ICF #3, Establishes & Maintains Agreements. Creating agreements is one of the first things coaches partner with clients on and these agreements set the foundation for partnering throughout the relationship.

The WHAT and HOW of Establishing and Maintaining Agreements

ICF Core Competency #3, Establishes & Maintains Agreements, is defined as:

Partners with the client and relevant stakeholders to create clear agreements about the coaching relationship, process, plans and goals. Establishes agreements for the overall coaching engagement as well as those for each coaching session.

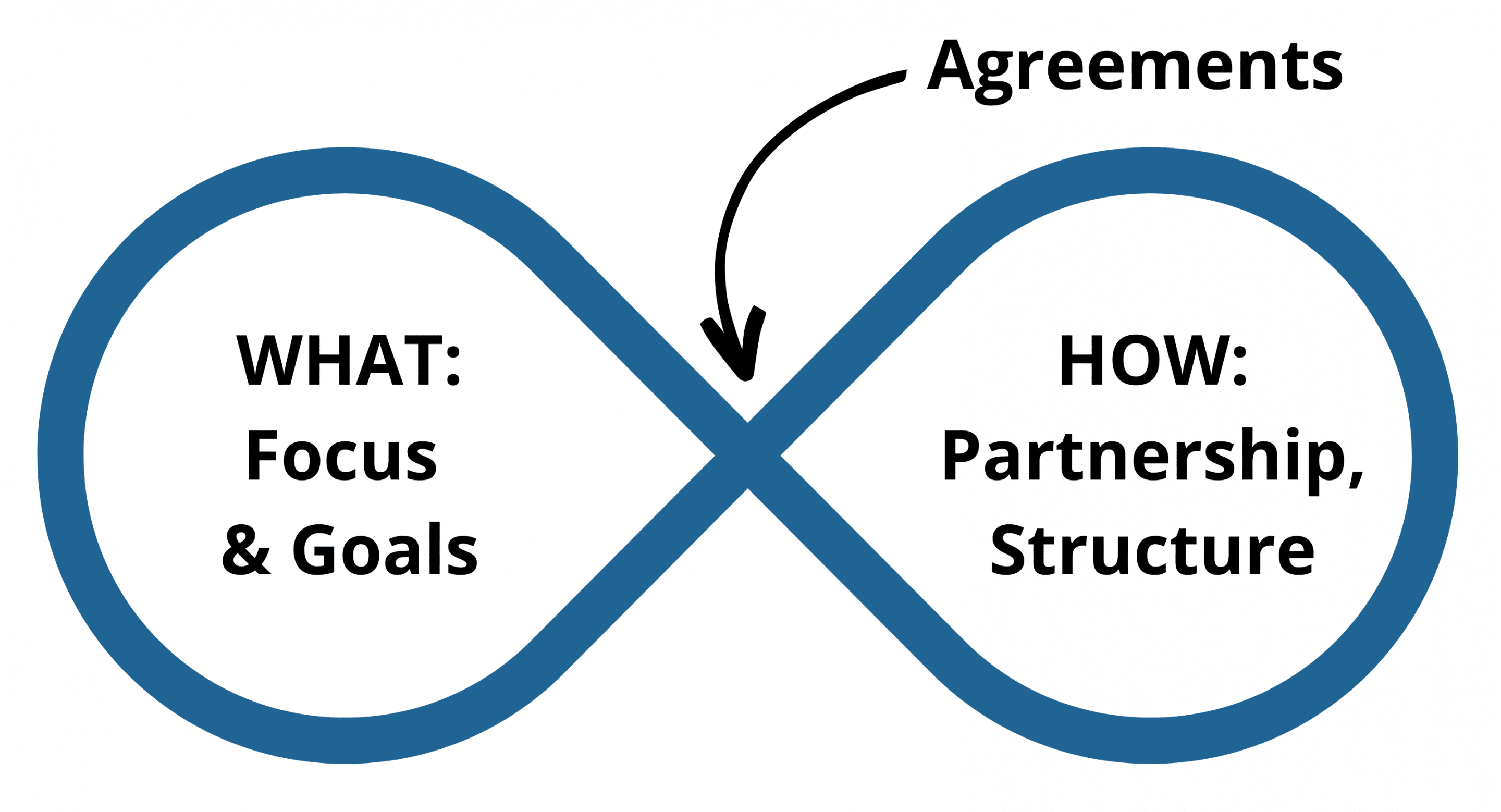

Examining the definition and the many subcompetencies for ICF #3 suggests that these agreements between coach and client fall into two themes:

-

- WHAT: This is the topic(s) the client wants to bring to coaching. For the coach, WHAT encompasses a contextual understanding of the new goals, learning, and growth the client desires over the course of the coaching engagement, as well as a specific focus for WHAT the client wants to achieve in individual sessions. (Relates to Subcompetencies 3.4, 3.6, 3.10)

- HOW: This refers to the structures and processes the coach and client will use over the course of the coaching engagement and within each coaching session. These can include logistics such as frequency, session length, and duration of the engagement, as well as how the coach and client will partner to communicate, relate, and explore the session focus and outcome. (Relates to Subcompetencies 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.5, 3.7, 3.8, 3.9, 3.11)

WHAT and HOW can be imagined as an infinity loop that coach and client continuously revisit in partnership.

As greater clarity emerges for the client, new agreements will be made on WHAT the coaching will focus on and HOW coach and client will explore movement toward the client’s goals. This dance between WHAT and HOW emphasizes the nature of partnership between coach and client. At different points in the conversation, emphasis will be on the WHAT, and in other places on the HOW.

Although WHAT and HOW are relevant to both the overall coaching engagement and individual coaching sessions, we will primarily reference WHAT and HOW as it relates to individual coaching sessions.

The Tension in Change

Although clients come to coaching wanting something new, change carries an inherent tension: the brain wants something new, but the brain also wants to avoid the many uncertainties associated with change.

Excessive uncertainty is perceived as a threat by the brain, and threats can come in many shapes and sizes. For example, our clients’ brains may be consciously or unconsciously processing uncertainties relating to these questions:

-

- Success: Do I have the capability to make this change?

- Rewards: Will this bring me what I’m hoping for?

- Meaning: Is this truly what I want?

- Timelines: How long will the change take?

- Support: Will I find the ideas and answers I need to maneuver around roadblocks?

- Relationships: Will the people I care about support or approve of the changes I’m making?

- Costs: Do I have sufficient resources to make the change, such as the finances or physical/emotional energy to persevere?

- Loss: How will I feel about the things I’m giving up to make this change?

- Sustainability: Will I be able to maintain the new behaviors I’m learning?

Brain circuitry and chemistry come into play when uncertainty strikes:

-

- Circuitry: It may be that the brain does not yet have existing neural circuitry to figure out how to move forward. Another possibility is that the stress of change has caused the brain to forget that there are resources and answers for how to move forward.

- Chemistry: The lack of answers can amp up a neurochemical cascade of cortisol and adrenaline, where we are more easily stressed and worried.

When answers are missing (circuitry) and emotions are on edge (chemistry), we operate in the Red Zone. In this state, the client’s energy is directed toward fight-flight activities, where they are not at their best.

Conversely, greater clarity between coach and client on the WHAT and HOW of the coaching agreement can lessen uncertainty and shift the brain-body toward the Blue Zone. In this state, coach and client partner to channel energy toward being curious, intentional, and proactive about how to move through the uncertainties of change.

The Neuro Nugget Behind Agreements

With all the unpredictabilities impacting the brain, we can sum up the essence of a neuro-coach approach to ICF #3 in this manner:

Agreements refocus energy

toward desired change.

With this in mind, we’ll explore several neuroscience concepts that shed light on how the brain influences change, and how agreements can lessen the uncertainties associated with change and channel the client’s energies toward meaningful change.

Specifically, we’ll look at:

-

- Seeking: The brain of every human is wired with the basic emotional need to seek (e.g., food, shelter, relationships, professional rewards). Uncertainty is inherent in seeking because we must both determine what we need, and consider how hard it will be to obtain these needs.

- Predictions: The brain has a strong predisposition to anticipate what will happen in the future. When uncertainty is high, negative predictions can create worry and increase stress.

- Attention: On most days, the brain is bombarded with inputs vying for our attention, causing us to be uncertain about what to focus on. The ability to filter distractions and focus on meaningful goals brings clarity for how to move forward.

- Safety: A sense of psychological safety can help restore calm and focus in the midst of uncertainty and change.

Seeking: The Brain’s Core Emotional Need

Human brains are hardwired with basic emotional systems, as delineated by neuroscientist and psychobiologist Jaak Panksepp. Among these, the “seeking” system ranks highest (additional systems in the brain’s emotional-affective networks include rage, fear, lust, care, and grief). Seeking is the inherent drive to explore our environment.

Mark Solmes, a psychoanalyst and neuropsychologist, asserts that this seeking instinct is not merely a luxury but a necessity for survival. It fuels our ability to meet fundamental needs like food and shelter, as well as complex ones like forging meaningful relationships and engaging in fulfilling work.

Seeking States

The brain’s seeking system operates in a variety of states from under-stimulated to over-stimulated, which can be linked to our concept of Red Zone | Blue Zone:

-

- Blue Zone: In a Blue Zone state, the brain’s seeking system is functioning optimally. We have the energy, interest, and curiosity to seek for the things we desire.

- Red Zone: In a Red Zone state, chronic stress can send the seeking system into either a depressed state or an overactive state. In these states, we either do not have the energy to seek or, at the other end of the spectrum, the energy directed toward seeking manifests as impulsive behaviors and manic thoughts.

Seeking behavior ties to WHAT the client brings to coaching. We often see the seeking drive manifest when clients express a desire for growth and improvement. It can be a very strong and clear drive towards a new goal, or it may be a curious interest or subtle sense of longing for something new. In addition, it may be a sense of dissatisfaction, which can be a precursor to identifying new goals.

Incorporating Seeking into Agreements

-

- WHAT: choosing a “seeking” topic that is meaningful or important (relates to ICF subcompetency 3.6)

- HOW: identifying an outcome that will lessen the client’s uncertainty on how to move toward their desired change (relates to ICF subcompetency 3.7 and 3.8)

The two-fold process of agreeing on WHAT and HOW brings direction to the conversation. Direction is a form of clarity and reduces some of the uncertainty the client is experiencing. As things become clearer, new or strengthened neural connections are being created inside the brain!

Predictions: Managing Future Expectations

As clients desire WHAT their preferred future will hold, their brains will also be predicting HOW uncertainties will unfold.

When predictions are made, the brain calculates both external and internal probabilities:

-

- External: The external probability weighs the probability that a desired outcome will follow certain choices and actions.

- Internal: The internal probability weighs whether we have the ability to perform on the actions.

External probabilities are associated with WHAT the client desires (the outcome of the goal), while internal probabilities are associated with HOW the client will move towards this desire. For instance, a leader might have a goal of a 30% increase in sales. In this example, the external prediction is that the sales increase will bring about desired results, such as increased profitability or improved market position. The internal prediction involves an assessment of the leader’s personal ability to execute strategy and motivate team members.

The Degree of Uncertainty Impacts Predictions

The brain and body will react differently depending on the stakes involved in the uncertainty. Donald Hebb, considered the father of neuropsychology, proposed that a certain amount of discrepancy between predictions and outcomes is pleasurable. For instance, we can feel a sense of excitement when predicting whether we’ll enjoy a new restaurant that we’ve read good reviews about. The energy associated with this type of uncertainty might be felt as fun and excitement.

However, when the stakes are high, uncertainty can lead to anxiety. High-stakes scenarios can send the brain-body into a Red Zone threat state. In the earlier example, if the 30% sales increase is a time-crunched “do-or-die” business goal where the stakes might involve the client staying employed or getting fired, the energy can quickly turn toward nervousness, fear, or panic.

Predictions and Agreements

An awareness of the brain’s predisposition for predictions (especially when stakes are high) can help us create meaningful coaching agreements. We can be curious about potential predictions the client has around external and internal probabilities, exploring them in the coaching framework of WHAT and HOW.

WHAT: Exploration around the client’s external probabilities might involve coaching questions such as these:

-

- What do you anticipate this goal will bring to you?

-

- How will achieving the goal be meaningful?

-

- What do you expect will be different when this is achieved?

-

- How will you be different as a leader as a result?

-

- What do you think needs to be addressed to make this possible?

-

- What is making this particularly challenging or complex?

-

- What do you see as the biggest roadblock associated with moving forward?

-

- What would need to change in the way you’re approaching this?

-

- How are your strengths/values playing into this?

-

- What would give you a sense that you’ve got this?

As coaches, we hold a view of the client as creative and resourceful. Our questions during the establishment of agreements can help reinforce this truth within the client, so that they also see themselves in this light. When this happens, they can make predictions that are founded within their wisdom and resourcefulness.

Attention: Steering the Course

Joe Dispenza, author of Breaking the Habit of Being Yourself, articulately captures the importance of attention:

“Where you place your attention

is where you place your energy.”

This “attention-energy loop” helps us recognize that:

-

- Positive Focus Brings Positive Energy: When attention is focused on meaningful activities and predictions of successful outcomes are high, the attention–energy loop will be life-giving and uplifting. Neurochemicals associated with positive emotions (oxytocin, dopamine) support operating in a flow state.

- Negative Focus Brings Negative Energy: Conversely, when attention is focused on irrelevant tasks and predictions of failure are strong, it can be disheartening and anxiety-producing. Neurochemicals associated with negative emotions (cortisol, adrenaline) can send us into a fight-flight state.

Given the information-saturated world in which we live, it takes conscious effort to focus our attention.

Unconscious and Conscious Processing Speeds

Our brains continuously process vast amounts of information. The body sends millions of bits of data to the brain every second, which is processed on an unconscious level. Although unconscious processing is thought to be in the millions of bits per second, conscious processing is dramatically less: some scientists measure it at only 2 to 60 bits per second for attention, decision-making, perception, motion, and language.

Given the brain’s bandwidth limitations for conscious processing, it is clear that we should be judicious in what we give attention to and how we pay attention.

Attention and Anxiety

Attention is influenced by both internal and external factors. External stressors (deadlines, conflict) or internal stressors (exhaustion, pain) can impair attention, leading to an increase in anxiety. Yale researchers discovered that neural circuits responsible for self-control are highly vulnerable to even mild stress.

A heightened state of alertness is normal when making change. With new territory to navigate, the brain naturally scans the environment for signs of danger and pays attention to potential threats. The brain is wired to give attention to threats, and understandably so, since being able to react to dangerous circumstances can help keep us alive.

The challenge arises when we give too much attention to situations that are perceived as threatening, but are actually harmless. This attentional bias toward potential threats increases anxiety. Without the ability to regulate our reactions, we can find ourselves in an endless loop of giving too much attention to anxiety-producing experiences.

When higher-order thinking shuts down, primal impulses go unchecked and mental paralysis can set in. Understanding these interactions allows us to consciously direct attention to the areas that best serve our objectives, enhancing our ability to cope with uncertainty and change.

Attention and Agreements

-

- WHAT: If the client’s attention is scattered or devoted to things that are not meaningful or important, energy will likely be deflated or diffused.

The coach can curiously and compassionately notice what is capturing the client’s attention. With this awareness, the coach can partner to assure that the topic the client is giving attention to within the coaching session is meaningful to the client. - HOW: If the client’s attention is focused on actions or outcomes beyond their scope of influence, energy will likely be frustrated or depressed. The coach can partner to assure that the client is giving attention to session outcomes that are within the client’s control.

- WHAT: If the client’s attention is scattered or devoted to things that are not meaningful or important, energy will likely be deflated or diffused.

As the coach brings Blue Zone energy to partnering on session focus, it invites the client to step out of Red Zone anxiety and shift their attention-energy towards opportunity.

Safety: The Bedrock of Change

Psychological safety is the shared belief that we can be honest, admit mistakes, voice opposing opinions, or ask “stupid” questions— all without the fear of negative consequences.

The absence or presence of psychological safety affects us on multiple levels:

-

- Absent in the Red Zone: When psychological safety is absent, the brain-body perceives threat and reacts accordingly. Threat causes an imbalance in the neural circuitry involved in thinking, decision-making, and mood. A temporary imbalance is normal—systems can be activated to react (jump out of the path of an oncoming car). A prolonged imbalance is detrimental (misreading benign behaviors as threatening).

- Present in the Blue Zone: When psychological safety is present, the brain-body can focus and feel calm, even amidst uncertainty. Energy is freed up and can be channeled toward strategic and proactive behaviors that support change—behaviors such as exploration, vulnerability, risk-taking, collaboration, and more.

Just as our minds give attention and energy to a topic, our bodies do the same. A prolonged threat state causes the brain-body to concentrate on and channel energy toward dealing with dysregulated brain circuitry and overly taxed metabolic and immune systems. Conversely, a psychologically safe state diffuses the stress associated with change, freeing energy to focus on creating new thinking and behaviors that support change.

Safety and Agreements

In this space, coach and client can partner on the WHAT and HOW of meaningful agreements:

-

- WHAT: The coach conveys, and the client understands, that there is safety to bring a session focus that may feel vulnerable. The client trusts there will be no negative consequences for revealing mistakes, mis-steps, insecurities, or other sensitive concerns. Exploration of topics that are vulnerable and uncertain often leads to break-throughs toward change.

-

- HOW: The coach gives space to the client to own the direction of the session, bringing respect and non-judgmental support to the client’s unique process for navigating the uncertainties inherent in change.

In a professional coaching context, an environment of safety enhances cognitive function and relational connection, supporting the client to set meaningful goals, address uncertainties, and make progress toward change. We will explore the neuroscience behind safety more deeply in our next article on ICF #4, Cultivates Trust and Safety.

Conclusion

-

- Seeking: encouraging a client’s natural instinct to seek and explore

- Predictions: helping clients manage predictions and uncertainty

- Attention: holding focus on the client’s desired change

- Safety: fostering a sense of psychological safety

Coaches can effectively empower clients to navigate through the inevitable uncertainties of life towards the change they desire. Partnering to continually align on WHAT the focus of coaching is and HOW to approach the goals collaboratively lays the foundation for the Blue Zone of connection and creation.

Susan Britton, PCC, is founder and president of The Academies for Coaching Inc., providing coaching education globally since 2001. For nearly 10 years, The Academies has been a leader at the intersection of coaching and neuroscience, with a commitment to curate and synthesize neuroscience findings into accessible, memorable, and effective coaching tools. Learn more about The Academies passion for “Changing Minds, for Good” at www.TheAcademies.com, where you can receive short, bi-weekly installments of “Encourage Your Brain”!

Our Courses

We offer all neuroscience-based programming; courses in career, leadership and strengths.

Encourage Your Brain!

Sign up for a free, short, brain-friendly newsletter that is guaranteed to make you feel better every Friday!